LUND, SWEDEN—According to a statement released by Lund University, DNA analysis of bone and teeth samples from prehistoric human remains unearthed in Denmark suggests that the first farmers to arrive in Scandinavia some 5,900 years ago wiped out the hunter-gatherer population within a few generations. “This transition has previously been presented as peaceful,” said Anne Birgitte Nielsen of Lund University. “However, our study indicates the opposite. In addition to violent death, it is likely that new pathogens from livestock finished off many gatherers,” she added. Then, some 4,850 years ago, seminomadic domestic cattle herders from southern Russia with Yamnaya ancestors entered Scandinavia and replaced those early farmers. This may have also occurred through violence and disease, Nielsen explained. Today’s Scandinavian population in Denmark can be traced to a mix of the Yamnaya and Eastern Europe’s Neolithic people. “We don’t have as much [ancient] DNA material from Sweden, but what there is points to a similar course of events,” Nielsen said. Read the original scholarly article about this research in Nature. For more, go to “Europe’s First Farmers.”

LUND, SWEDEN—According to a statement released by Lund University, DNA analysis of bone and teeth samples from prehistoric human remains unearthed in Denmark suggests that the first farmers to arrive in Scandinavia some 5,900 years ago wiped out the hunter-gatherer population within a few generations. “This transition has previously been presented as peaceful,” said Anne Birgitte Nielsen of Lund University. “However, our study indicates the opposite. In addition to violent death, it is likely that new pathogens from livestock finished off many gatherers,” she added. Then, some 4,850 years ago, seminomadic domestic cattle herders from southern Russia with Yamnaya ancestors entered Scandinavia and replaced those early farmers. This may have also occurred through violence and disease, Nielsen explained. Today’s Scandinavian population in Denmark can be traced to a mix of the Yamnaya and Eastern Europe’s Neolithic people. “We don’t have as much [ancient] DNA material from Sweden, but what there is points to a similar course of events,” Nielsen said. Read the original scholarly article about this research in Nature. For more, go to “Europe’s First Farmers.”

Autore: admin

Freedom Fort

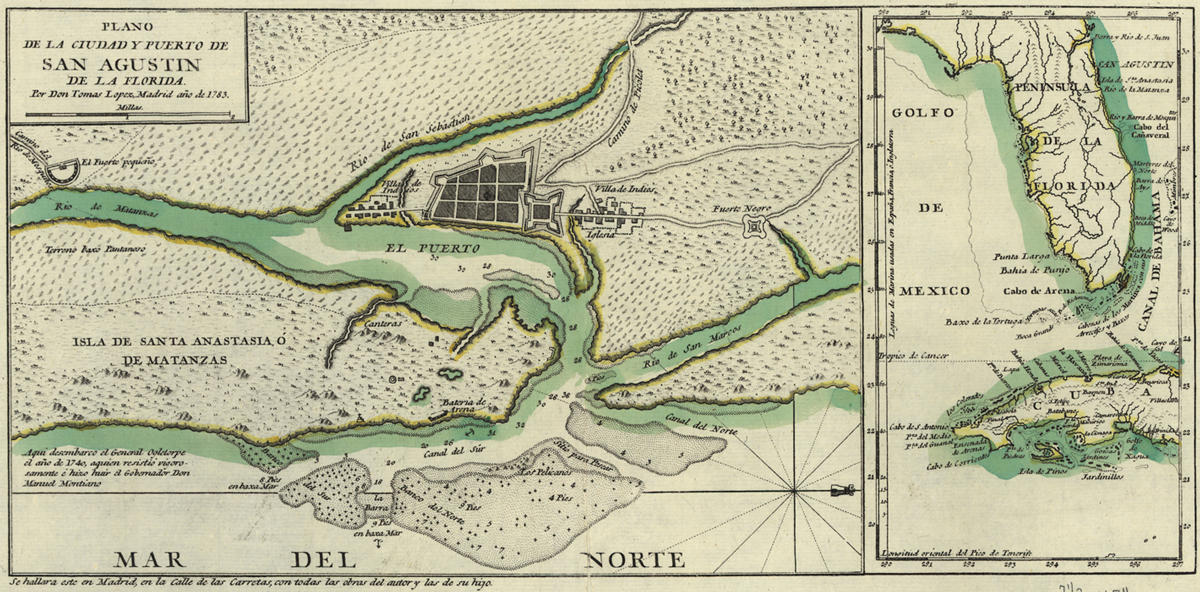

An eighteenth-century map shows the plan of St. Augustine, the capital of the Spanish colony of Florida. The location of Fort Mose, which was established in 1738 and was home to a militia consisting of men who had escaped enslavement in the English colonies to the north, is labeled Fuerte Negro.

In 1715, a Mandinga man from the Gambia region of West Africa who would go down in history under the name Francisco Menéndez escaped from enslavement in the English colony of South Carolina to join up with local Native Americans, the Yamasee, who were waging war against his former captors. Menéndez fought alongside the Yamasee for a few months. At times, the Yamasee came close to driving the English out of the Carolinas, but superior colonial reinforcements eventually arrived. Later in 1715, Menéndez and several other formerly enslaved people, likely including his Mandinga wife, guided by their Yamasee comrades, traveled south toward St. Augustine, the capital of the Spanish colony of Florida. They had heard that the Spanish king had promised freedom to people fleeing slavery—provided they converted to Catholicism.

Enslaved people seeking liberty had sought refuge in St. Augustine since at least 1687, when eight men, two women, and a young child arrived by boat from the Carolinas. An edict issued by Spain’s King Charles II (reigned 1665–1700) in 1693 giving “liberty to all” formalized the Spanish policy of welcoming formerly enslaved people, and their numbers increased as word of the proclamation spread. Menéndez’s journey to freedom, however, was interrupted when a Yamasee man known as Perro Bravo, or Mad Dog, claimed ownership of him and several others who had fought against the English in the Carolinas. The acting governor of Florida purchased the hostages, and Menéndez was later sold at auction to the royal accountant, Francisco Menéndez Márquez, whose name he adopted at his Catholic baptism. The royal accountant became Menéndez’s godparent and entrusted him with a great deal of responsibility. Still, Menéndez filed multiple petitions with Spanish authorities protesting his continued enslavement, to no avail. “Even though he’s in a very important household, that of one of the most important officers in St. Augustine, Menéndez is still not free like he is supposed to be,” says historian Jane Landers of Vanderbilt University.

Relations between the Spanish and English colonies were always tense and often erupted into armed conflict. By offering escaped slaves their freedom, the Spanish struck an economic blow against the English, depriving them of a valuable labor force. They took advantage of the new arrivals’ hatred of their former English enslavers to strike a military blow as well. “Who would be more resistant to the British than those who had been enslaved by them?” asks Landers. In 1726, Florida Governor Antonio de Benavides appointed Menéndez commander of a newly formed militia composed of formerly enslaved people. This fighting force played a key role in defending St. Augustine against an English invasion in 1728.

More than 100 escapees had made their way from the English colonies to St. Augustine by 1738. That year, a new Florida governor, Manuel de Montiano, reviewed Menéndez’s latest petition, which included testimony from a Yamasee leader regarding his bravery in the fight against the English in South Carolina and blaming his continued enslavement on the “infidel” Mad Dog. Montiano granted unconditional freedom to Menéndez and other escapees who had been re-enslaved in Florida. The governor also moved Menéndez’s militia to a newly established town two miles north of St. Augustine that he named Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, known today as Fort Mose. There, the militia would serve as the northernmost defenders of the Spanish colonial capital against British attacks.

The initial settlement at Fort Mose was decidedly small-scale. The walls of the square fort were made of earth and logs and measured just 70 feet or so on a side. The fort was surrounded by a moat and contained a lookout tower and a fortified house. In historical terms, however, Fort Mose looms large. It was the first legally sanctioned free Black town in the lands that would become the United States and thus holds great resonance for the area’s Black community today. “This was the first underground railroad,” says Landers. “And it went south, not to Canada.”

Portrait of an Ancient Ax

Cutting tools known as Acheulean hand axes, made by Homo erectus and other early human species from about 1.76 million to 130,000 years ago, represent humanity’s most enduring technology. They are particularly plentiful at the Tanzanian site of Isimila, the subject of a lecture Dartmouth College art historian Steve Kangas attended in 2021. The shape of the tools seemed familiar to Kangas, and he approached his colleague, paleoanthropologist Jeremy DeSilva, with a startling observation. To Kangas, the Acheulean hand axes in the lecture looked uncannily like a strangely shaped rock depicted in the fifteenth-century painting Étienne Chevalier with Saint Stephen by French artist Jean Fouquet. DeSilva agreed, and they collaborated with University of Cambridge archaeologists Alastair Key and James Clark to test out the idea.

Key and Clark compared the shape, color, and surface details of the stone in the painting with those of Acheulean hand axes found in northern France, where Fouquet lived and worked. They determined that the characteristics of the stone depicted by Fouquet did indeed strongly resemble those of the Paleolithic artifacts. Key says that while they cannot definitively prove that Fouquet selected a prehistoric stone tool to include in his painting, their conclusions make it seem highly likely that he did so. Based on late medieval sources, people of Fouquet’s time knew Acheulean hand axes as “thunderstones” and believed they were created by lightning strikes. The revelation that they were, in fact, created by prehistoric people lay more than 300 years in the future.

AFRL’s XQ-67A makes 1st successful flight

WRIGHT-PATTERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Ohio (AFRL) – The Air Force Research Laboratory’s Aerospace Systems Directorate successfully flew the XQ-67A, an Off-Board Sensing Station, or OBSS, uncrewed air vehicle Feb. 28, 2024, at the General Atomics Gray Butte Flight Operations Facility near Palmdale, California.

The XQ-67A is the first of a second generation of autonomous collaborative platforms, or ACP. Following the success of the XQ-58A Valkyrie, the first low-cost uncrewed air vehicle intended to provide the warfighter with credible and affordable mass, the XQ-67A proves the common chassis or “genus” approach to aircraft design, build and test, according to Doug Meador, autonomous collaborative platform capability lead with AFRL’s Aerospace Systems Directorate. This approach paves the way for other aircraft “species” to be rapidly replicated on a standard genus chassis.

This new approach also responds to the challenge of great power competition by speeding delivery of affordable, advanced capability to the warfighter.

“This approach will help save time and money by leveraging standard substructures and subsystems, similar to how the automotive industry builds a product line,” Meador said. “From there, the genus can be built upon for other aircraft — similar to that of a vehicle frame — with the possibility of adding different aircraft kits to the frame, such as an Off-Board Sensing Station or Off-Board Weapon Station, [or OBWS].”

So, what is an autonomous collaborative platform?

“We broke it down according to how the warfighter sees these put together: autonomy, human systems integration, sensor and weapons payloads, networks and communications and the air vehicle,” Meador said.

“We’ve been evolving this class of systems since the start of the Low Cost Attritable Aircraft Technologies, [or LCAAT], initiative,” he added.

The major effort that initially explored the genus/species concept was the Low Cost Attritable Aircraft Platform Sharing, or LCAAPS, program, which fed technology and knowledge forward into the OBSS program that culminated with building and flying the XQ-67A, Meador said.

“The intention behind LCAAPS early on was these systems were to augment, not replace, manned aircraft,” said Trenton White, LCAAPS and OBSS program manager from AFRL’s Aerospace Systems Directorate.

In late 2014 and early 2015, the initial years of the LCAAT initiative, the team began with some in-house designs, for which Meador credits White, who led the studies early on that evolved into the requirements definition for the Low Cost Attritable Strike Demonstrator, or LCASD, Joint Capability Technology Demonstration. The LCASD team defined, designed, built and tested the XQ-58 for the first time in 2019.

“The first generation was XQ-58, and that was really about proving the concept that you could build relevant combat capability quickly and cheaply,” White said.

The OBSS program built upon the low-cost capability that LCASD proved by leveraging design and manufacturing technology research that had taken place since the first generation and was directed to reduce risk in the development of future generations, White added.

“We had always intended from the start of LCAAT to have multiple vehicle development spirals or threads of vehicle development,” White said. “Then once the vehicle is proven ready, you can start integrating stuff with it, such as sensors, autonomy, weapons, payloads and electronics.”

With the XQ-67A, the team is using the platform-sharing approach or drawing leverage from automotive industry practices.

“We are looking to leverage technology development that’s been done since XQ-58, since that first generation,” White added.

With advancements in manufacturing technology since the XQ-58, the team aimed to use that system and the technology advancements to create a system design with lower cost and faster build in mind.

“It’s all about low cost and responsiveness here,” White said.

The team began discussing LCAAPS in 2018, focusing on the notion of “can we provide the acquirer with a new way of buying aircraft that is different and better and quicker than the old traditional way of how we build manned aircraft,” Meador said. “Which means we pretty much start over from scratch every time.”

Instead, the team considered the same approach that a car manufacturer applies to building a line of vehicles, where the continuous development over time would work for aircraft, as well.

“It’s really about leveraging this best practice that we’ve seen in the automotive and other industries where time to market has decreased, while the time to initial operating capability for military aircraft has increased at an alarming rate,” White said.

With this genus platform, White said a usable aircraft can be created faster at a lower cost with more opportunities for technology refresh and insertion if new models are being developed and rolled out every few years.

AFRL harnesses science and technology innovation for specific operational requirements to ensure meaningful military capabilities reach the hands of warfighters. The XQ-67 is the first variant to be designed and built from this shared platform, White said.

“The main objectives here are to validate an open aircraft system concept for hardware and software and to demonstrate rapid time-to-market and low development cost,” he added.

This project looked at incorporating aspects of the OBSS and the OBWS to different capability concepts. The OBSS was viewed as slower while carrying sensors but have longer endurance, while the OBWS was considered faster and more maneuverable, with less endurance but better range.

“We wanted to design both of those but figure out how much of the two you can make common so we could follow this chassis genus species type of approach,” Meador said.

XQ-67A has been just over two years in the making, moving quickly through the design, build and fly process. While the team initially worked with five industry vendors, AFRL decided at the end of 2021 to exercise the opportunity to build the General Atomics design.

This successful flight is initial proof that the genus approach works, and aircraft can be built from a chassis.

“This is all part of a bigger plan and it’s all about this affordable mass,” Meador added. “This has to be done affordably and this program — even though there’s an aircraft at the end that we’re going to get a lot of use out of — the purpose of this program was the journey of rapid, low-cost production as much as it was the destination of a relevant combat aircraft.”

This signals to other companies that there is a new approach to constructing an aircraft, moving away from the conventional method of starting from scratch, Meador said.

“We don’t have the time and resources to do that,” Meador said. “We have to move quicker now.”

Out of Sight: How Museums Can Harness the Blind Perspective to Enrich Visitor Experiences

For museum professionals, dissatisfaction like this can be difficult to swallow. We like to think of our institutions as places for respite, learning, and enjoyment. We want our audiences to be challenged and delighted and for our institutions to become cherished within our communities. But are we fulfilling our missions and visions when audiences are leaving frustrated due to the inability to access the information we are presenting? Should positive experiences be a rarity for some parts of our community? Is it equitable for certain audiences to have to work for the same access that others do not? I would hope the answer to these questions would be a resounding no.

Nonetheless, the blind and visually impaired community remains a chronically underserved group in museums, due to a reliance on largely visual exhibition design elements. This dependency on the visual can make content inaccessible to these visitors, who make up an estimated seven million people in the US alone, causing them to feel disappointed or unwelcome.

By integrating the blind perspective into their practices and elevating their accessibility measures, museums can reach wider and more diverse audiences, making negative experiences fewer and further between. But in order for this to be possible, our institutions must first shift away from seeing those who have disabilities as an outlying “problem” that needs a special solution. Instead, we need to think holistically about the interplay between visitors and our environment, across a wide spectrum of ability. When a person with a disability is having trouble within a designed environment, it often means that those without disabilities are too. In that sense, harnessing the perspectives of people with disabilities can reap universal benefits, helping point to limitations in our visitor experience that might be weakening it for everyone.

This effect can be especially potent when applied to blind audiences, since a reliance on visual information is so ingrained in museum practices. To illustrate how museums can transform their work when they integrate this perspective, this post shares examples of institutions that have done so using a variety of techniques, which other museums can emulate for the benefit of all visitors.

Example 1: The Museum of the Gateway Arch

A recent renovation allowed the Museum of the Gateway Arch in St Louis, Missouri, to become a more welcoming environment where all visitors feel they can take ownership of the space. To achieve this outcome, the museum implemented universal design (UD), defined as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” The principles of UD are as follows:

- Equitable use: The design is usable by people with a variety of ability levels.

- Flexibility in use: The design acknowledges a range of abilities and preferences.

- Simple and intuitive use: The design should be easy for anyone to understand, regardless of their prior knowledge.

- Perceptible information: The design communicates necessary information to the individual regardless of their sensory abilities.

- Tolerance for error: The design takes into account that individuals may make mistakes during its use. Employing this principle lessens negative consequences, unintended actions, or hazards during the experience.

- Low physical effort: The design can be used comfortably by anyone with minimal fatigue or difficulty.

- Effective size and space for approach and use: The design is an appropriate size for anyone who may interact with it. This might mean having adjustments for a user’s size, shape, and mobility level.

To employ these principles, exhibition designers at the museum developed multiple means of forming connections with history, allowing visitors to explore through both sight and touch. For example, the museum provides a tactile model of the Gateway Arch and its surrounding grounds, situating visitors with visual and touchable elements representing structures, plants, and walking paths. Another model features a metal buffalo figurine coupled with a piece of mounted fur, so that visitors can understand both the form and texture of the animal. The museum also has plans to incorporate audio guidance in future exhibitions. UD has allowed visitors at the Museum at the Gateway Arch to have a more hands-on learning experience while also crafting a space that is more accessible to visitors with a variety of disabilities, including the blind community.

Example 2: Tiflológico Museum (Museum for the Blind)

Established in 1992, the Tiflológico Museum in Madrid, Spain, aims to serve visually impaired visitors through primarily tactile exhibition elements. It advertises itself as a museum that is meant to be both seen and touched, providing components that align closely with UD principles. This is a major contrast to a typical museum experience, often decorated with “do not touch” signs to deter viewers from handling objects within the galleries. While the space is catered toward blind individuals, all visitors are encouraged to participate in touch-based installations that explore both art and architecture. This includes reproductions of well-known monuments as well as tactile pieces created by blind artists displayed with vibrant colors and raised patterns. In addition to these models, the museum presents devices that have been used by the blind community throughout history, giving sighted viewers an understanding of the assistive technology that is essential for visually impaired users. By centering itself around the blind experience, the Tiflológico Museum has become a unique and interactive space that can be enjoyed by all groups of visitors.

Example 3: The High Museum of Art

An example of an immersive museum experience that draws upon the blind perspective is Outside the Lines at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia. Outside the Lines is an immersive maze experience created by Bryony Roberts, an architect, designer, and scholar, and Monica Obinski, the High Museum’s Curator of Decorative Arts and Designs. The designers worked closely with the Center for the Visually Impaired in Atlanta to create the installation, leading them to incorporate a variety of textures and textiles, encouraging all visitors to touch, experience, and play within the maze. While the design is visually intriguing, it does not rely on the visual to engage and immerse visitors. Roberts describes the space as “active, unpredictable, and multi-sensory…crossing the lines that are often drawn between the experiences of people with disabilities and without disabilities, in public space.” With accessibility standards, UD principles, and the blind perspective in mind, museum professionals can create meaningful and inclusive immersive exhibitions similar to Outside the Lines for the enjoyment of all audiences.

Example 4: National Gallery of Prague

Another example of exhibition design informed by the blind experience is the National Gallery Prague’s 2018 Touching Masterpieces exhibition. For Touching Masterpieces, Geometry Prague and NeuroDigital partnered with the museum and the Leontinka Foundation for the blind and visually impaired to transform its best-known sculptures into virtual objects that could be felt through haptic glove technology. When visitors wore them, the gloves vibrated and gave feedback to mimic what it might feel like to run your hands over the artworks. While the project was specifically designed to give blind individuals the most accurate representation of the 3D objects as possible, it created a fuller experience for all visitors, giving them access to a sensory experience they would not otherwise have. As one participant in the exhibition put it in a video published by Geometry Prague:

“Art is not always explainable just by words. The element of touching it and feeling it is missing…reading about it is not the full experience. It shouldn’t be.”

Though this specific technology is not as easily applied to most two-dimensional artworks, there are similar technologies available for translating visual information into tactile equivalents. Likewise, while a virtual reality experience such as this one may not be realistic for every museum, lower-tech alternatives coupled with audio description might have a similar impact.

Conclusion

By acknowledging and embracing the blind perspective, museums and cultural institutions can move towards greater cultural inclusivity while also improving exhibition design and enjoyment for everyone. The case studies within this article use universal design, assistive technology, and virtual reality to create more well-rounded and multi-sensory experiences for all visitors. When design elements are developed to reach beyond sight alone, audiences have the opportunity to participate in more enhanced experiential learning. The experience of blindness can provide a unique and nuanced perspective to the museum environment, enhancing visitor engagement and allowing audiences to develop even deeper connections with the objects and stories found within our exhibition spaces.