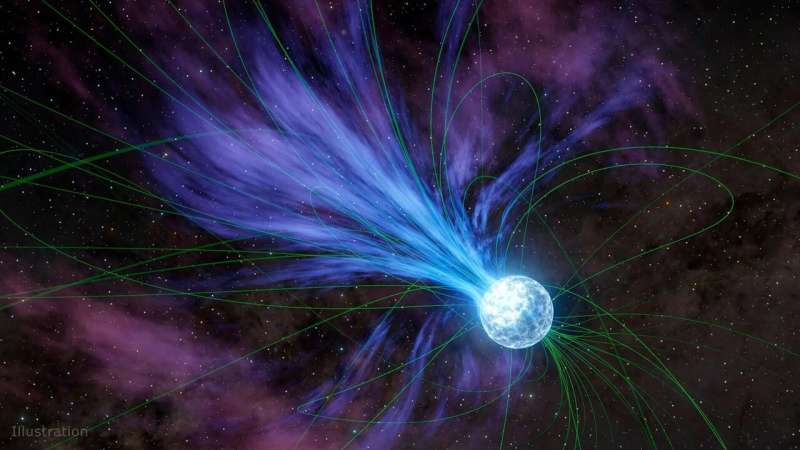

In an ejection that would have caused its rotation to slow, a magnetar is depicted losing material into space in this artist’s concept. The magnetar’s strong, twisted magnetic field lines (shown in green) can influence the flow of electrically charged material from the object, which is a type of neutron star. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

What’s causing mysterious bursts of radio waves from deep space? Astronomers may be a step closer to providing one answer to that question. Two NASA X-ray telescopes recently observed one of such events—known as a fast radio burst—mere minutes before and after it occurred. This unprecedented view sets scientists on a path to understand these extreme radio events better.

While they only last for a fraction of a second, fast radio bursts can release about as much energy as the sun does in a year. Their light also forms a laser-like beam, setting them apart from more chaotic cosmic explosions.

Because the bursts are so brief, it’s often hard to pinpoint where they come from. Prior to 2020, those that were traced to their source originated outside our own galaxy—too far away for astronomers to see what created them. Then a fast radio burst erupted in Earth’s home galaxy, originating from an extremely dense object called a magnetar—the collapsed remains of an exploded star.

In October 2022, the same magnetar—called SGR 1935+2154—produced another fast radio burst, this one studied in detail by NASA’s NICER (Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer) on the International Space Station and NuSTAR (Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array) in low Earth orbit.

The telescopes observed the magnetar for hours, catching a glimpse of what happened on the surface of the source object and in its immediate surroundings before and after the fast radio burst. The results, described in a new study published in the journal Nature, are an example of how NASA telescopes can work together to observe and follow up on short-lived events in the cosmos.

The burst occurred between two “glitches” when the magnetar suddenly started spinning faster. SGR 1935+2154 is estimated to be about 12 miles (20 kilometers) across and spinning about 3.2 times per second, meaning its surface was moving at about 7,000 mph (11,000 kph). Slowing it down or speeding it up would require a significant amount of energy.

That’s why study authors were surprised to see that in between glitches, the magnetar slowed down to less than its pre-glitch speed in just nine hours, or about 100 times more rapidly than has ever been observed in a magnetar.

“Typically, when glitches happen, it takes the magnetar weeks or months to get back to its normal speed,” said Chin-Ping Hu, an astrophysicist at National Changhua University of Education in Taiwan and the lead author of the new study. “So clearly, things are happening with these objects on much shorter time scales than we previously thought, and that might be related to how fast radio bursts are generated.”

Spin cycle

When trying to piece together exactly how magnetars produce fast radio bursts, scientists have a lot of variables to consider.

For example, magnetars (which are a type of neutron star) are so dense that a teaspoon of their material would weigh about a billion tons on Earth. Such a high density also means a strong gravitational pull: A marshmallow falling onto a typical neutron star would impact with the force of an early atomic bomb.

The strong gravity means the surface of a magnetar is a volatile place, regularly releasing bursts of X-rays and higher-energy light. Before the fast radio burst that occurred in 2022, the magnetar started releasing eruptions of X-rays and gamma rays (even more energetic wavelengths of light) that were observed in the peripheral vision of high-energy space telescopes. This increase in activity prompted mission operators to point NICER and NuSTAR directly at the magnetar.

“All those X-ray bursts that happened before this glitch would have had, in principle, enough energy to create a fast radio burst, but they didn’t,” said study co-author Zorawar Wadiasingh, a research scientist at the University of Maryland, College Park and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “So it seems like something changed during the slowdown period, creating the right set of conditions.”

What else might have happened with SGR 1935+2154 to produce a fast radio burst? One factor might be that the exterior of a magnetar is solid, and the high density crushes the interior into a state called a superfluid. Occasionally, the two can get out of sync, like water sloshing around inside a spinning fishbowl. When this happens, the fluid can deliver energy to the crust. The paper authors think this is likely what caused both glitches that bookended the fast radio burst.

If the initial glitch caused a crack in the magnetar’s surface, it might have released material from the star’s interior into space like a volcanic eruption. Losing mass causes spinning objects to slow down, so the researchers think this could explain the magnetar’s rapid deceleration.

But having observed only one of these events in real time, the team still can’t say for sure which of these factors (or others, such as the magnetar‘s powerful magnetic field) might lead to the production of a fast radio burst. Some might not be connected to the burst at all.

“We’ve unquestionably observed something important for our understanding of fast radio bursts,” said George Younes, a researcher at Goddard and a member of the NICER science team specializing in magnetars. “But I think we still need a lot more data to complete the mystery.”